Being Adaptive, Attentive and Responsible on the Road

As is the case with other road user groups, the person behind the steering wheel plays a key role in road traffic accidents involving goods transport vehicles. Driver assistance systems offer tremendous potential for preventing accidents. For this to actually be the case, however, drivers need to know exactly what the systems can and cannot do. In view of the numerous requirements, strains and dangers, training for professional drivers is extremely important.

Whether a driver is at the wheel of a truck, in the driver’s cab of a locomotive, the cockpit of a cargo plane or on the bridge of a container ship – when it comes to the “human factor,” reliability plays a key role. Experts refer to “behavioral reliability” in the context of human–machine interaction – in this case, interaction with the means of transport. Behavioral reliability depends on the design of the technical system and the performance requirements of the person in question.

As a general rule, behavioral reliability is particularly high when the respective system is optimally adjusted to the capabilities of the person. If errors occur, they are considered to be the consequence of an incompatibility between the individual and the task of driving the means of transport. The problem is that human error can have fatal consequences on the road, so it is important to maintain or, where necessary, increase one’s level of behavioral reliability. To do this, one has to be or become aware of influencing factors.

When a driver is at the wheel of a motor vehicle, influencing variables relating to the human factor primarily include acquired skills in handling the vehicle system (competency), the mental and physical requirements of driving a vehicle (fitness to drive) and the current physical and mental state (capability). With truck cabs featuring an increasing number of automation functions, the requirements regarding the required level of competency, fitness to drive and, where applicable, capability need to be modified or even completely redefined.

Training for professional drivers

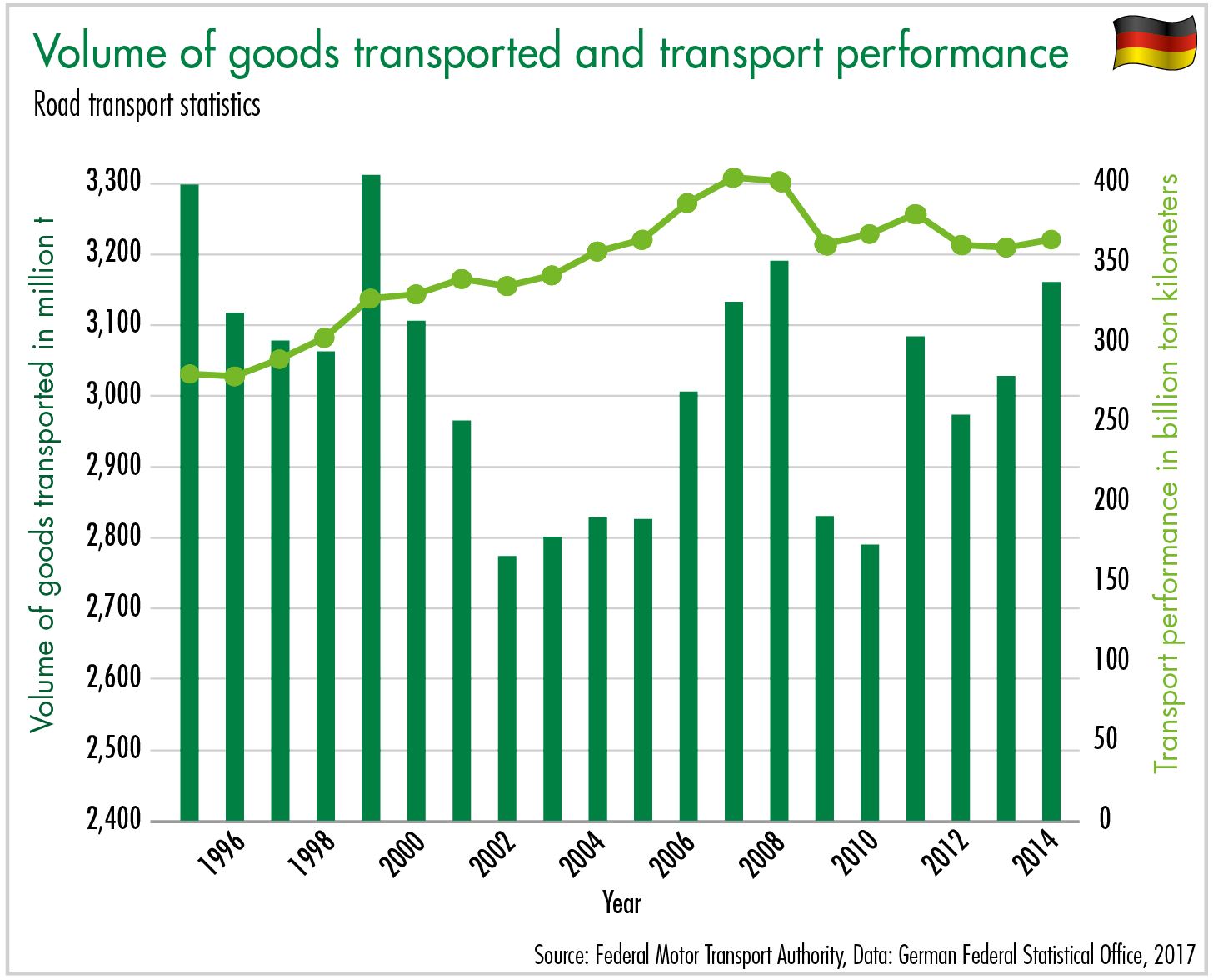

Given increasing goods transportation by road, the demand for professional drivers has increased. Against this backdrop, questions regarding the safety of truck and bus transport operations are coming to the fore. Professional drivers in particular have to fulfill very specific requirements due to the complexity of their driving task. Professional drivers face difficult conditions – including driving along unfamiliar routes, on poor roads or in challenging weather conditions – more often than car drivers. Technical equipment in goods transport and passenger transport vehicles is often on a higher level; while this is much better in terms of road safety, it also places increased demands on drivers. Truck drivers need to know exactly how driver assistance systems work and how these systems assist them in their job so that they can take the appropriate action in the event of a technical malfunction. Professional drivers also have to adhere to a range of transport regulations regarding the safe securing of loads or the transportation of dangerous goods. When transporting goods long distances across international borders, professional drivers are additionally confronted with a number of country-specific traffic regulations and features that they have to deal with appropriately. In addition to this, there is the emotional and mental stress of constant time pressure and being a long way from one’s family. Another particular challenge for truck drivers is the physical stress involved in working long shifts or single- handedly loading and unloading goods.

The main cause of accidents is still driver error. To increase road safety and help professional drivers to maintain good health, ongoing training is essential. In Germany, it is possible to undergo state-approved training to become a professional driver. In 2016, 2,964 training contracts were signed. According to the Chambers of Industry and Commerce, around 2,000 trainees completed their professional driver training over the last three years, although there were over 100 fewer trainees between 2015 and 2016.

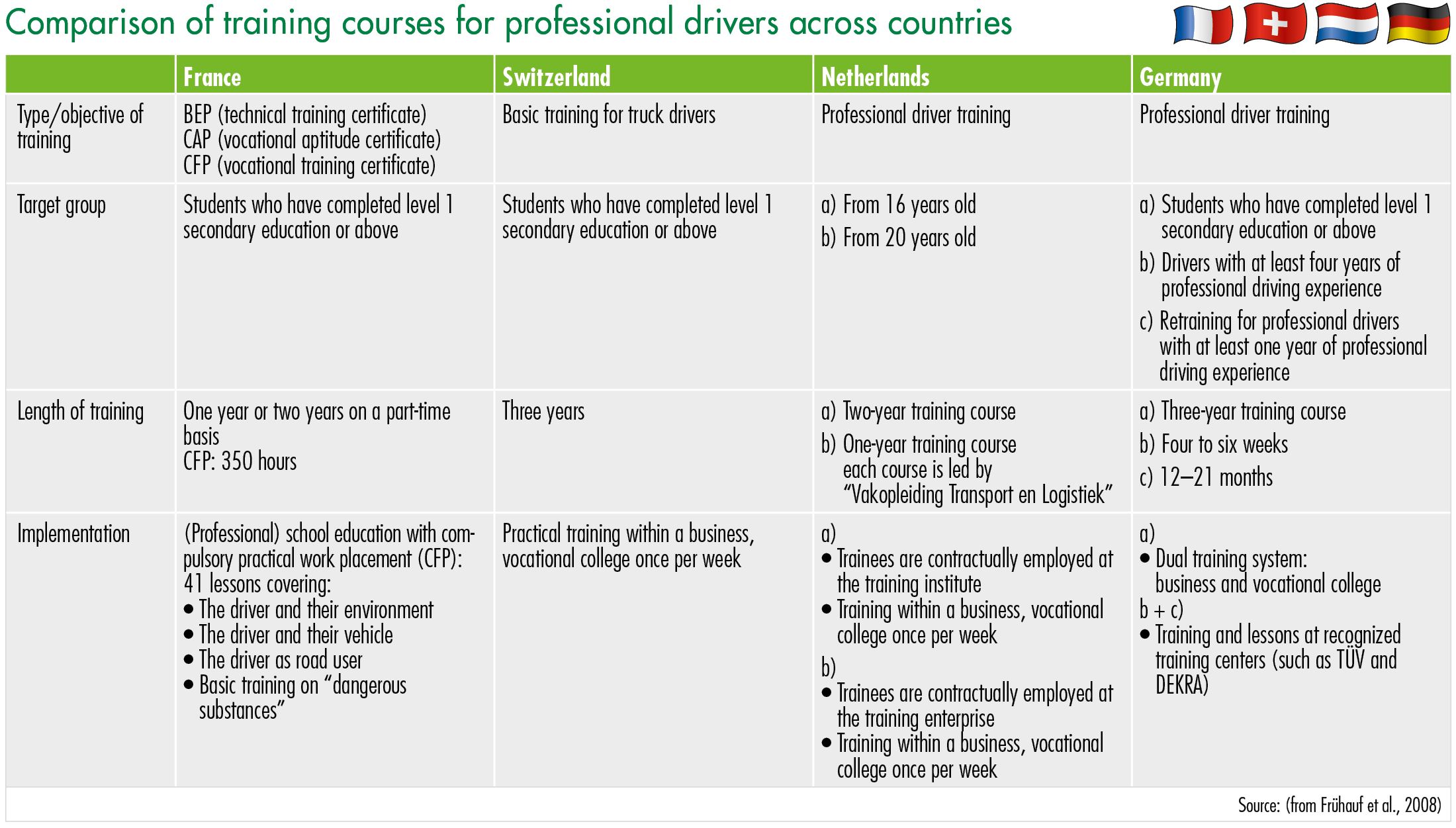

Training courses similar to the professional driver training offered in Germany are available in other European countries too. A report compiled by BASt (German Federal Highway Research Institute) in 2008 compared the professional training courses.

At a European level, Directive 2003/59/EC (EU directive concerning professional drivers) of July 3, 2003, defines the minimum requirements for professional drivers. The directive cites the following as the reason for professional driver training:

“To enable drivers to meet the new demands arising from the development of the road transport market, Community rules should be made applicable to all drivers, whether they drive as self-employed or salaried workers and whether on own account or for hire or reward.

The establishment of new Community rules is aimed at ensuring that, through their qualification, drivers are of a standard to have access to and perform the act of driving.”

The aim is to improve road safety either by making drivers complete an initial qualification over 280 hours or complete a four-hour theory test and a two-hour practical test in addition to regular further training over 35 hours every five years. The compulsory initial qualification is aimed at drivers from 18 to 21 years old with a driving license in classes C1, C1E, C, CE, D, DE, D1 and D1E. Eighteen-year-olds starting their career in the transport of goods with a driving license in class C1 or C1E and 21-year-olds with a driving license in class C or CE or D, DE, D1 or D1E can complete an accelerated initial qualification involving 140 hours of training and a final test.

The EU defines the minimum requirements to be met for the initial qualification and further training as:

• The safety rules to be observed while driving and while the vehicle is stopped

• The development of defensive driving, anticipating danger and making allowance for other road users

• Rational fuel consumption

• The development of defensive driving, anticipating danger and making allowance for other road users

• Rational fuel consumption

Officially approved training facilities are responsible for implementing qualification and training measures, which are completed by students once they have successfully completed the corresponding test.

Special demands regarding professional drivers

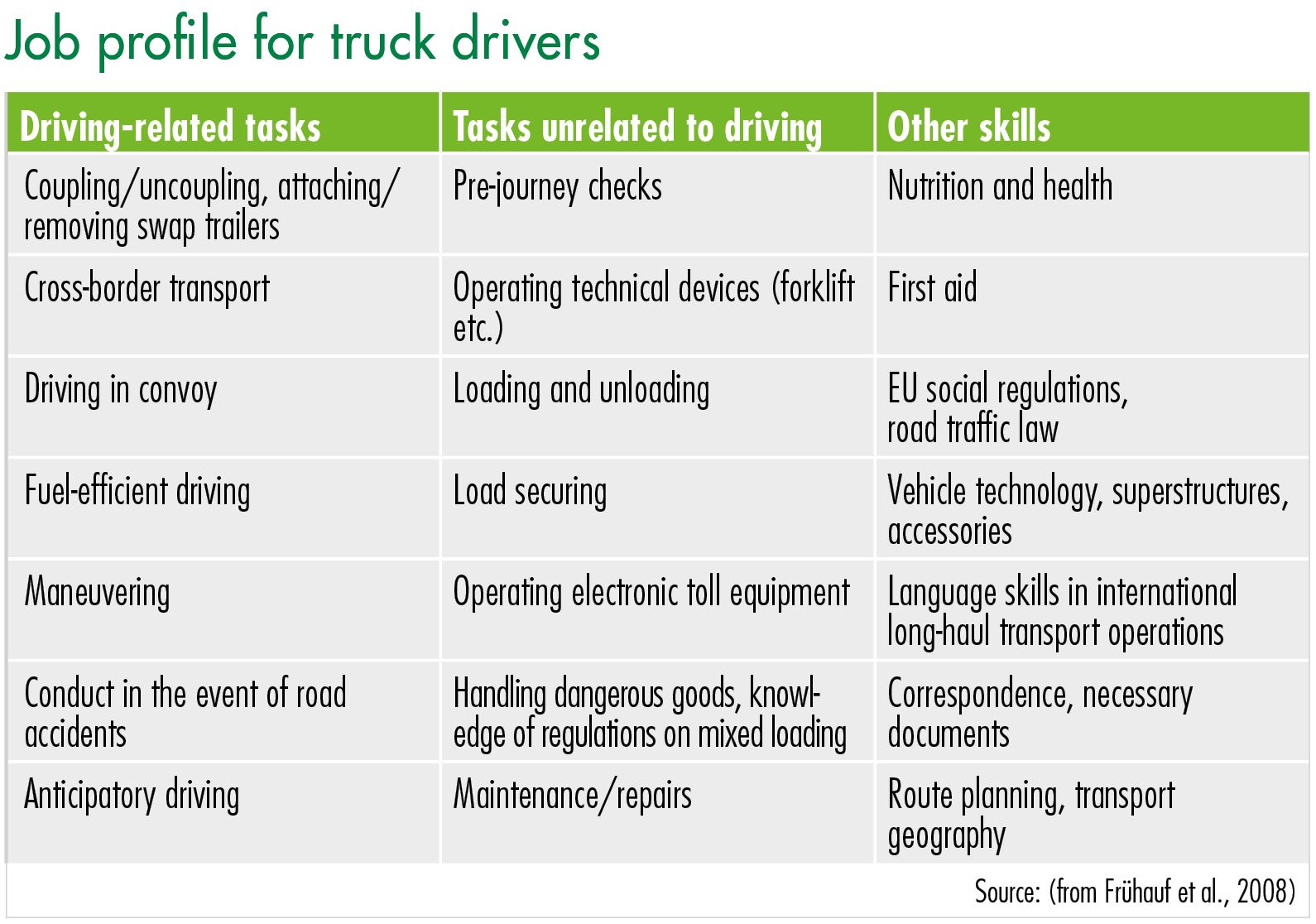

Demands regarding professional drivers have changed significantly in recent years. The job of professional drivers used to be defined simply as driving and loading/unloading. The fact that professional drivers in the goods transportation sector have to perform a range of other tasks was detailed by Frühauf and colleagues (2008); the authors distinguished driving-related tasks from non-driving-related tasks.

Various other skills and “soft skills” are also required because drivers are expected to be friendly and willing to compromise when dealing with colleagues and customers.

Due to the strict requirements regarding professional drivers in the goods transportation sector in Germany, other provisions apply in addition to the initial qualification in order to attain the appropriate driving license. According to the regulation on driver’s licenses (“FeV”), professional drivers must meet certain physical requirements and have no visual impairments. For drivers who transport people professionally, psychophysical capability (ability to withstand stress, sense of orientation, concentration, attention and reaction capability) is also tested.

In 2000, section 2.5 “Anforderungen an die psychische Leistungsfähigkeit” (Requirements regarding mental capacity) of the “Begutachtungsleitlinien zur Kraftfahreignung” (Guidelines for assessing fitness to drive) defined limit values for these dimensions, which are still applicable today, whereby the limit value of PR = 16 (group 1) and PR = 33 (group 2) (“PR” means “percentile rank”). This statistical measure indicates the relative position that a person occupies with regard to a particular characteristic in a comparative or reference group.

The notes accompanying the “Guidelines for assessing fitness to drive” specify that these definitions were established “taking empirical values into account.” Regarding the changes in traffic conditions, entailing the need for professional drivers to complete additional tasks while under ever-increasing time pressure, denser traffic and automation technology, we have to consider whether these guidelines are still applicable under these new conditions and what can be done to keep the human reliability factor in the human–vehicle system at the required high level in the long term.