DEKRA Study On Helmet Use Among Cyclists In Europe

In case of an accident, a helmet is a piece of safety equipment that can save a cyclist or motorcyclist’s life. The “Technology” section of this Report will look in more detail at how this works. For now, we want to look at figures for helmet use. A 2018 publication by the German Federal Highway Research Institute provides the numbers for Germany across different age groups. In 2018, almost 100 percent of riders of two-wheeled motor vehicles wore helmets. For cyclists, on the other hand, this number dropped to just 18 percent, although children (82 percent) were much more likely to wear a helmet than adults. The publication also compares these figures to those for the previous year, clearly showing that the trend for wearing a helmet is at least on the rise.

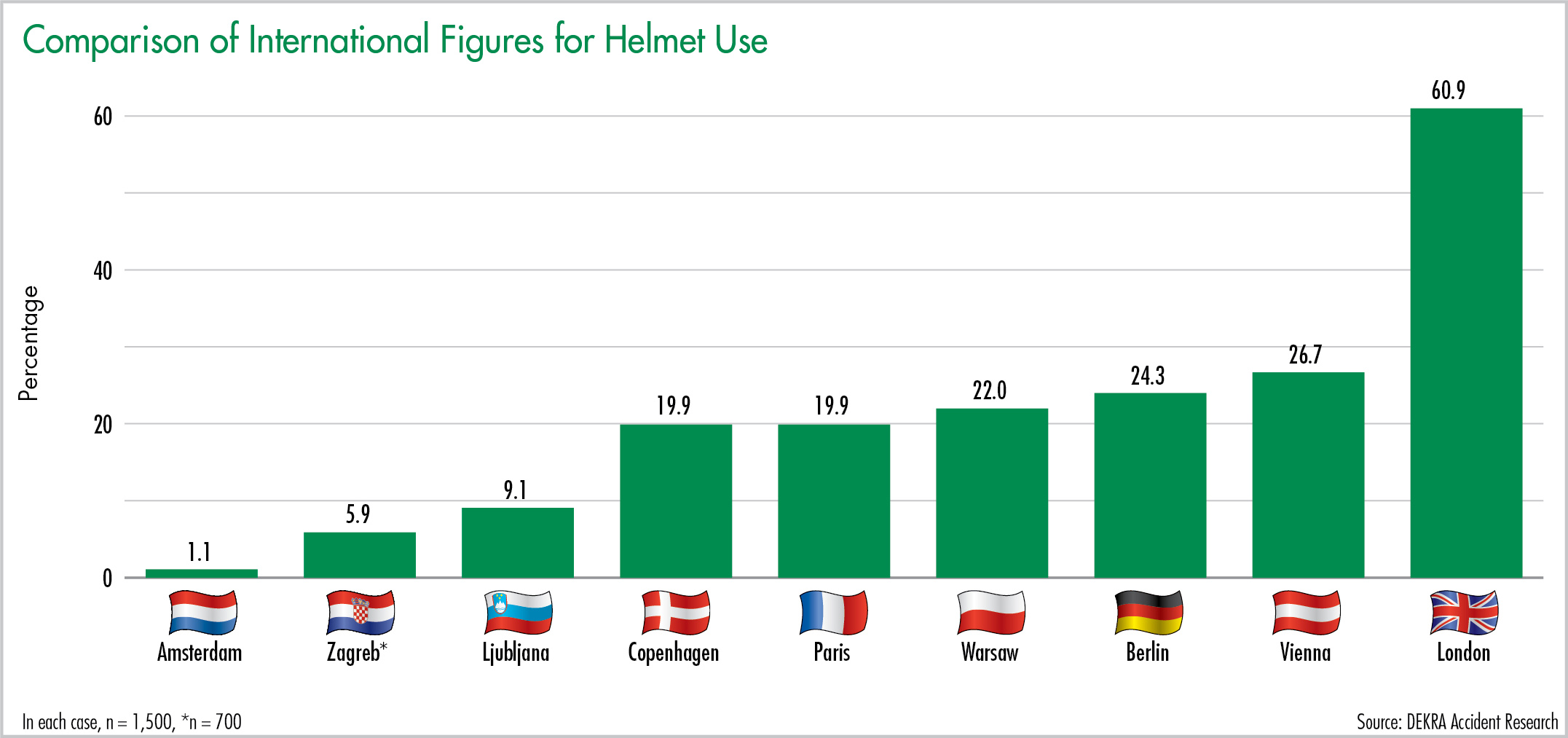

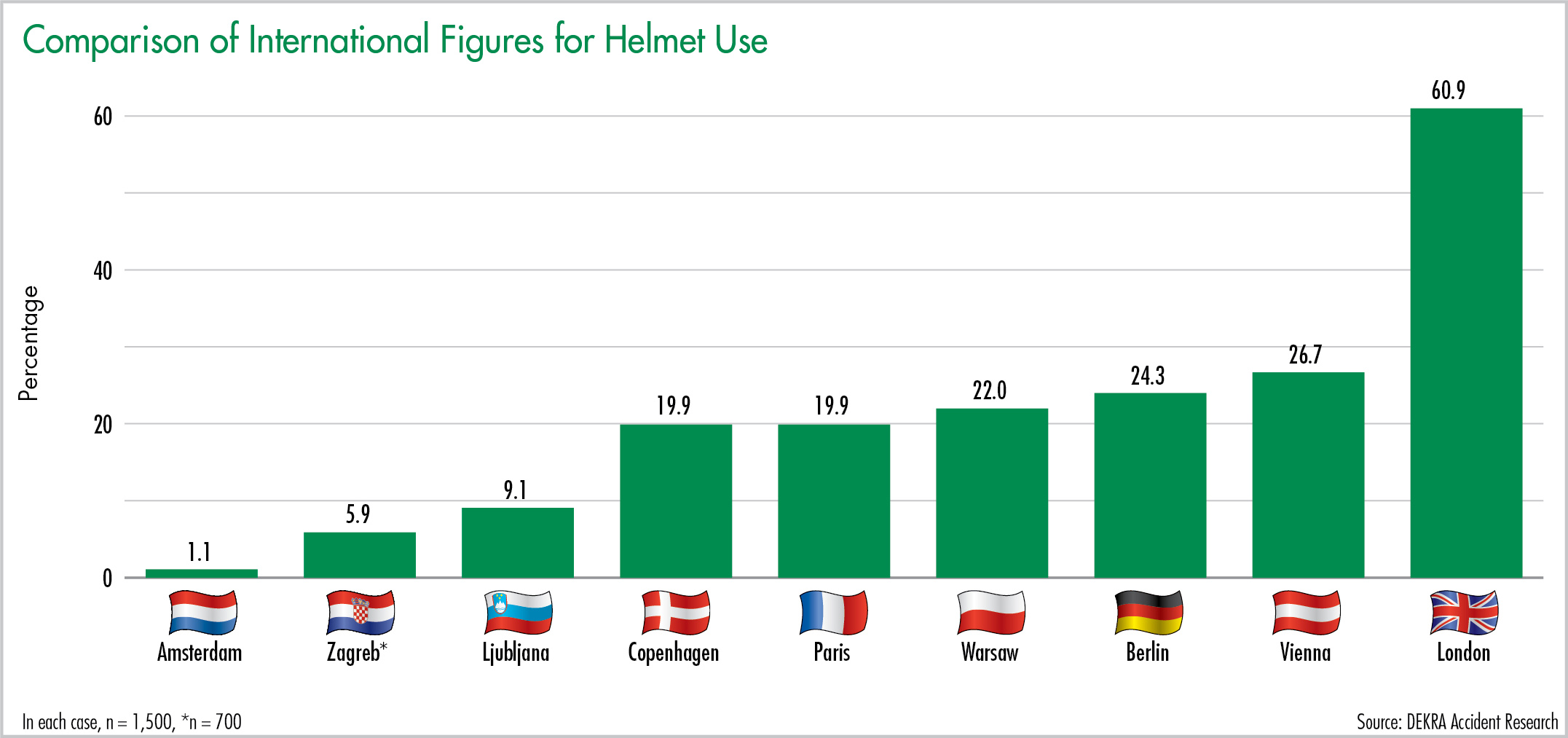

In order to determine the current helmet use figures for cyclists, pedelec riders, and e-scooter users, DEKRA Accident Research drew up a quantitative, cross-sectional study in 2019 to measure helmet usage in nine bike-friendly European capitals that had been selected: Berlin, Warsaw, Copenhagen, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Vienna, London, Amsterdam, and Paris. To ensure that the results were as representative as possible, the study observed bicycle traffic in each of the cities at different times of day, in different locations around the city center, and exclusively on weekdays. A pilot study had been conducted in Stuttgart.

ONE OF MANY RESULTSOF A DEKRA STUDY:IN LONDON, ALMOST61 PERCENT OF CYCLISTS WEAR A HELMET.

In total, 12,700 cyclists, pedelec riders, and scooter/e-scooter users across the nine selected capitals were checked for helmet use. Over all cities, 22 percent of riders were wearing one. As such, around one in five cyclists, pedelec riders and scooter/e-scooter users wore a helmet on the road. London recorded the highest helmet use by far at 60.9 percent, followed by Vienna at 26.7 percent, and Berlin at 24.3 percent. Amsterdam had the lowest helmet use, at just 1.1 percent. In Ljubljana and Zagreb, the figures were 9.1 and 5.9 percent respectively. In all of the cities in the study, most of the cyclists were using privately owned bicycles. The average helmet use among these cyclists was much higher than for persons on rented bicycles. E-scooters had a significant impact on the absolute usage figures, especially in Berlin, Warsaw, Vienna, and Paris. Helmet use on these vehicles was very low, and was far below the average helmet use figures overall for these cities. In Berlin, 173 e-scooters were recorded. None of the riders of these scooters were wearing helmets. In Paris, the situation was slightly better, with nine percent of the 316 e-scooter users in the study wearing a helmet.

The study also showed that children wore helmets more frequently when riding their bicycles than any other age group. This is doubtless mainly due to the fact that parents exercise greater caution when it comes to the safety of their children, and ideally act as role models. In addition to this, wearing a helmet is a legal requirement in the countries of four of the capital cities included in the DEKRA study: for children aged under 12 in Austria and France, under 15 in Slovenia, and under 16 in Croatia. In contrast to this, the lowest figures for helmet use were recorded among teenagers. This group was more likely to be cycling with friends or on their own than with their parents. The fact that many in this group did not wear helmets may be caused by their development during puberty. During this phase, teenagers often do the opposite of what parents and society recommend.

A BICYCLE HELMET CAN HELP TOPREVENTSEVERE INJURIES.

INFRASTRUCTURE IS AN IMPORTANTFACTOR IN WHETHER CYCLISTS FEEL SAFE AND/OR WEAR A HELMET

Other city-specific observations: Since many residents of London see the British capital’s roads as dangerous for cyclists, many of them wear a helmet on their way to work. During data collection, it was also noted that a large number of cyclists in London wear safety clothing, such as yellow high-visibility jackets that enable them to be seen better in traffic.

The Netherlands are seen as “the” country for cyclists. In light of this, it seems confusing at first glance that the investigation in Amsterdam showed that just 1.1 percent of the city’s cyclists wear helmets. Look more closely, however, and it makes sense. After all, the state began investing heavily in suitable infrastructure to make the country’s roads safer for cyclists back in the 1970s. In 1975, The Hague and Tilburg be-came the first model cities for bicycle boulevards, while Delft was the first city to install a complete network of bicycle paths. In the Netherlands, the bicycle plays a bigger everyday role in traffic than in almost any other country. The infrastructure development is unparalleled, and due to this the population feels safe when cycling. As such, helmets are seen as an unnecessary burden, and the idea of making them a legal requirement dismissed. Overall, the Netherlands and Denmark are two of the safest countries in the world for cyclists in terms of mileage.

Copenhagen is often compared to Dutch cities in terms of its bicycle traffic. In light of this, it is surprising that, at 19.9 percent, its rate of helmet use is much higher than the figure for Amsterdam, and in the middle bracket for all the cities included in the study. Alongside its well-developed infrastructure, Denmark also relies on largescale helmet use campaigns to increase safety. Unlike in Amsterdam, many of Copenhagen’s bicycle paths are not physically separated from car lanes except for by low curbs. This makes cycling in Copenhagen seem more dangerous, which is why cyclists there rely on helmets more than in Amsterdam.

In light of the results of this DEKRA study and the aforementioned figures from the German Federal Highway Research Institute, we need to determine the factors on which acceptance of wearing a bicycle helmet depends, and how we can improve this acceptance. Royal, S. et al. (2007) created a meta-analysis of eleven studies on types of intervention and their effects on helmet-wearing behavior among children and teenagers. The results show that non-legislative intervention and support measures that are not part of legal regulations can be very effective. In comparison to campaigns that originated in schools or used subsidized helmets as a promotional measure, campaigns that were conducted at the local community level close to people’s homes and involved the distribution of free helmets were far more effective. Interventions that comprised solely of educational work were the least effective. However, even these measures produced a significant, if smaller, improvement. Interventions in schools were most effective when they addressed younger students. This indicates that particular attention must be paid to this group. Nevertheless, and no matter what the age of the cyclist, even the best infrastructure cannot prevent accidents. And when accidents happen, a helmet remains an indispensable tool for protecting against injuries that can be severe or even fatal.