Retaining Mobility for as Long as Possible

All around the world, people are getting older. According to forecasts, one in four people in Europe and North America could be aged 65 or over by 2050, for example. At the same time, senior citizens are becoming increasingly mobile, and many are continuing to use the roads well into their later years, in a variety of ways. However, such mobility comes with a much higher risk for this demographic than for younger age groups. In order to minimize this risk while still enabling older people to remain mobile and active members of our society, there are a number of areas where action needs to be taken.

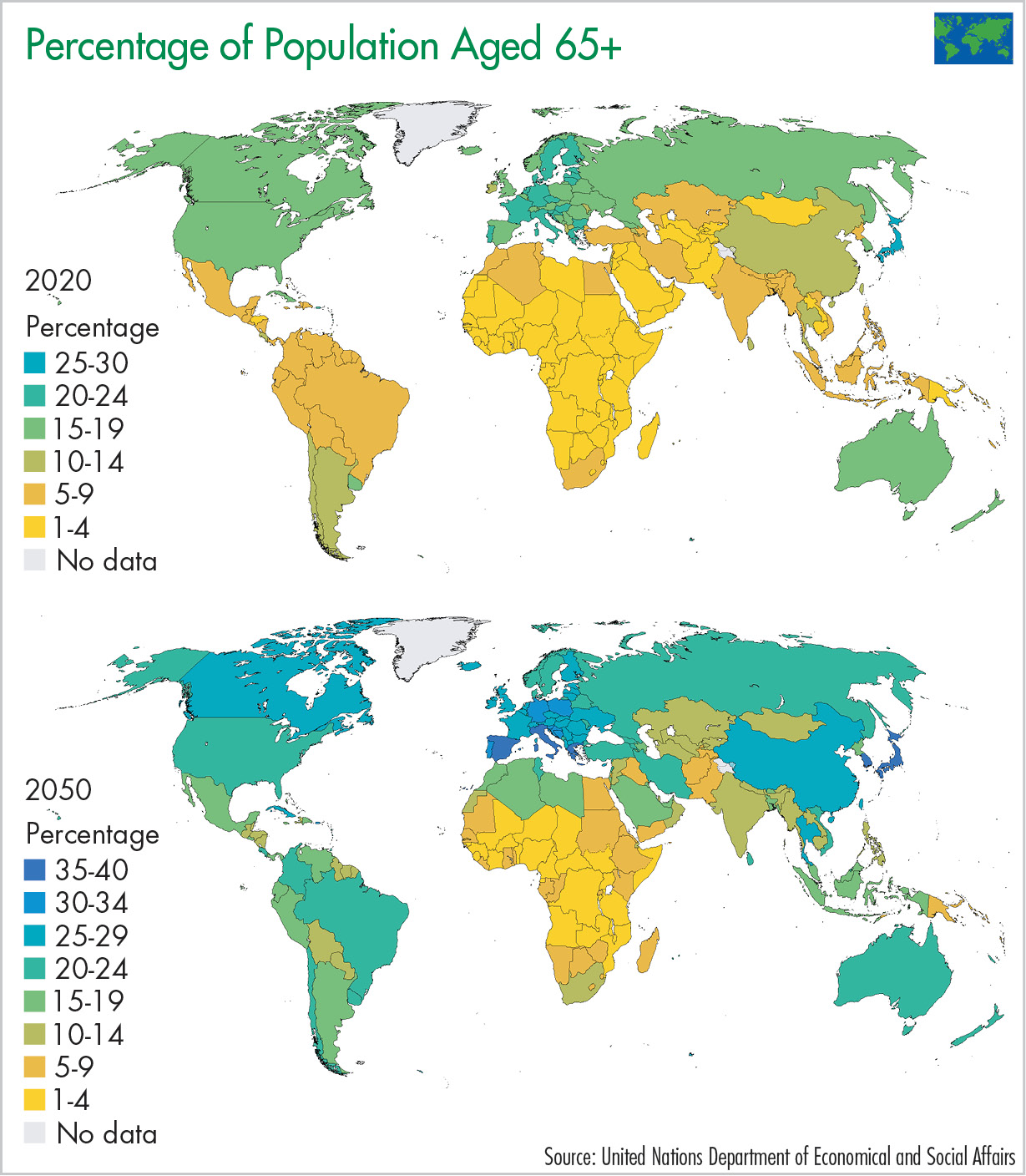

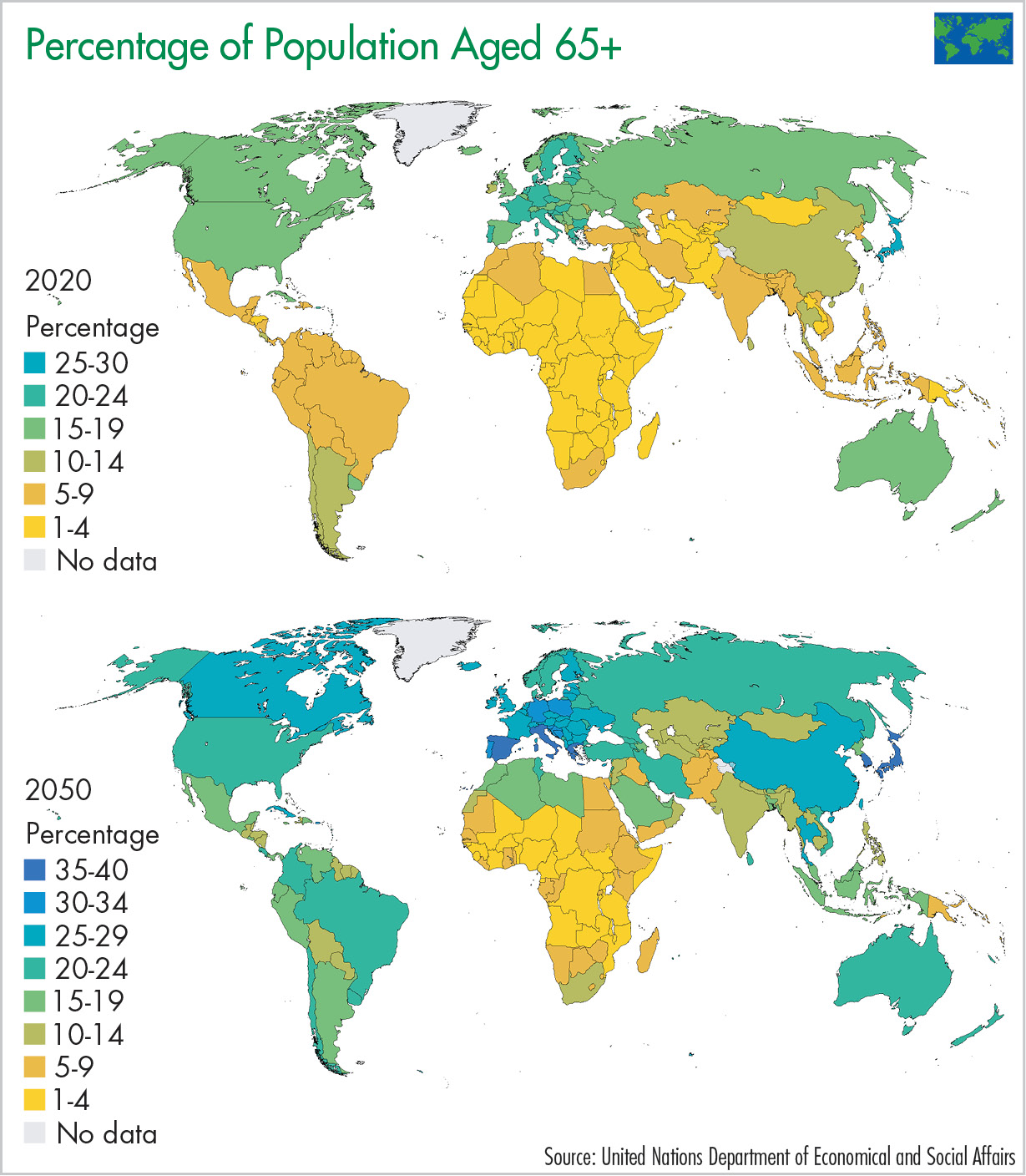

The facts and figures in the UN’s “World Population Prospects 2019” show that the global population is continuing to grow, and could rise from 7.7 billion in 2019 to as many as 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.9 billion in 2100. More than that, however, the publication also provides irrefutable evidence that our society is aging. While only one in eleven people were over the age of 65 in 2019, the forecast estimates that this will rise to one in six by 2050 (Figure 1).The regions in which the percentage of the population aged 65+ is expected to double between 2019 and 2050 include North Africa and West Asia, Central and South Asia, East and Southeast Asia, as well as Latin America and the Caribbean. In Europe and North America, as many as one in four residents could be aged 65 or over by 2050. At a global level, the number of people aged 80 or over is expected to triple – from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050. The average life expectancy, which rose from 64.2 to 72.6 years between 1990 and 2019, is ex-pected to reach around 77 by 2050.

GREATER RISK OF INJURYFOR SENIOR CITIZENS

The aging of the population will also lead to an increase in older road users, as stated in studies such as “ElderSafe – Risks and countermeasures for road traffic of the elderly in Europe,” which was published by the European Commission in December 2015. However, this also means that the number of senior citizens who run the risk of becoming involved in or causing road accidents due to factors such as functional limitations and increased fragility will increase as well. The dynamic nature of this development was made clear in an estimate made by the European Transport Safety Council (ETSC) in 2008, which examined the impact that an increase in the percentage of older peo-ple in the population would have on the number of traffic fatalities between the time of publication and 2050. Using figures from 2006, “Road Safety PIN Flash 9” came to the conclusion that, by 2050, one in three traffic fatalities in the European Union could be aged 65 or older. The figures from 2018 – a year in which senior citizens accounted for around 29 percent of all traffic fatalities in the EU – showed that this threshold had almost been reached already, more than 30 years earlier than predicted back in 2008.

The fact is that older people are at a disproportionate risk of getting injured when compared to younger road users. This is due first and foremost to the natural aging process and the resulting deterioration in bone and neuromuscular strength. This places older people at a much greater risk of suffering severe or even fatal injuries than a young person would be if involved in exactly the same accident. An article on the safety of older road users published in the UK in 2000 illustrated this in a number of ways, including a mortality index for different age groups. The article set the value for the 20 to 50 age group at 1.0, which increased to 1.75 for 60-year-olds, 2.6 for 70-year-olds, and reached be-tween 5 and 6 for persons aged 80 and over.

65+ AGE GROUP HAS LARGEST PERCENTAGE GROWTH

Another interesting resource on this topic are the figures collected for the EU Injury Database between 2005 and 2008 , which were re-produced without modification in the European Commission’s report “Traffic Safety Basic Facts 2018: The Elderly.” These indicate that 43 percent of all older victims of road accidents were taken to hospital – compared with just 32 percent of road accident victims overall. Whether or not a hospital stay was required also differed depending on what type of road user the patient in question was. The largest difference was in the number of injured car occupants: almost 50 percent of older people were taken to hospital after the car they were traveling in was involved in a road accident, compared to just under 25 percent of all road users in such situations. 42 percent of all the older people taken to hospital with injuries following a road accident had suffered broken bones – compared with just 27 percent of road accident victims overall.

In order to determine which parts of the body were most commonly injured among senior citizens involved in road accidents, DEKRA’s accident researchers analyzed several years’ worth of data from the German In-Depth Accident Study Data-base (GIDAS). The results showed that the percentage of pedestrians who suffered injuries to their lower extremities and the head was higher than that for car drivers. This is because pedestrians are generally hit in their lower extremities first, before their head subsequently collides with either the vehicle itself or the ground. Among car drivers, on the other hand, the most common part of the body to be injured apart from the extremities and the head was the thorax. When grading these injuries using the international Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), which ranges from AIS 0 for “Not injured” to AIS 6 for “Maximum” (i.e. untreatable), it is notable that senior citizen pedestrians incur a greater percentage of severe injuries than 18 to 64-year-old pedestrians. This applies particularly to head and lower-extremity injures for AIS 3 (Serious), particularly to thorax and abdomen injuries for AIS 4 (Severe), and to neck and thorax injuries for AIS 5 (Critical). There are also a number of figures that stand out with regard to older people who are injured while driving, such as those for AIS 3 head and thorax injuries.

MEASURES MUST NOT BE PUT OFF INDEFINITELY

PROACTIVE STRATEGY REQUIRED

In order to ensure that senior citizens can use the roads safely well into their later years, the European Commission’s aforementioned "ElderSafe" report lays out a comprehensive plan of action. This plan recommends that the following risk factors be turned into particular areas of focus: frailty, illnesses and functional limitations, medication intake, innercity roads, and senior citizenss pedestrians. According to the report, a proactive strategy is required at national, regional and local levels, and must cover a wide range of measures relating to issues such as infrastructure, driver safety training and practical evaluations, and vehicle technology.

When it comes to technology, there is no doubt that driver assistance systems offer great potential for either completely preventing accidents, such as those most commonly caused by driver errors, or at the very least minimizing their consequences. And as a survey commissioned by DEKRA has shown, senior citizens in particular are very open-mined when it comes to the use of electronic assistants. More details on this can be found in the Technology chapter of this report. Of course, it is important to note that it will take a long time for vehicles with assistance systems to achieve a high level of market penetration.

To help illustrate this point, if a new assistance system were to be installed in all newly registered cars in the EU with immediate effect, it would take more than eleven years until half of the cars on the road were fitted with this system. However, since there are also many years of evaluation and legislation processes between a system becoming ready for launch on the market and its installation becoming a legal requirement, it is likely to take around 20 years before half of all car drivers have any such system in their vehicles.

This means that, if we want to improve road safety as quickly as possible, especially for senior citizens, in order to help them retain their mobility for as long as possible, measures pertaining to physical infrastructure and the vehicles themselves can only be a secondary priority. Our main focus – as demonstrated in the following chapters of this report – must be on the human factor. At the same time, however, measures that will have a long-term impact must not be put off indefinitely.