Stress/pressures/distractions

According to the model developed by Matthews, stress occurs when environmental stressors such as poor visibility, poor road conditions, delays and personality factors interact. In subjective terms, stress is experienced as anxiety, anger or tiredness. As part of a survey (Evers, 2010) involving 555 truck drivers, the influence of stress and strains on the way drivers behave in traffic was investigated. The driver survey showed that drivers work for an average of 63.2 hours per week, with 46.6 hours spent driving. In 80.1 percent of cases, the drivers work in the long-distance transportation sector. Approximately one third of the drivers are commonly away from their homes for around one week. Drivers specified traffic conditions as a source of stress particularly frequently – above all, an inadequate number of places to rest, obstructive, risky or aggressive behavior on the part of other road users, poor roads, very dense traffic and traffic jams. Time issues are also sources of stress, however, both with regard to one’s personal life (leisure, family) and logistics (loading delay, poor route planning).

The fact that perceived sources of stress are also associated with a certain accident risk seems clear. This cannot easily be proved on the basis of accident statistics, however, because the cause of accidents is usually assumed to be that which the police determine when they are called to an accident. On the one hand, it can therefore be assumed that certain causes of accidents cannot be recorded statistically because the accidents are not recorded – for example, if minor damage occurs as a result of a single-vehicle accident. On the other hand, stress-induced situations that cause accidents – such as feeling distracted, anxious or tired – can be determined by police only with difficulty. Unlike for alcohol or drugs in the blood, no instrument for measuring these factors is available.

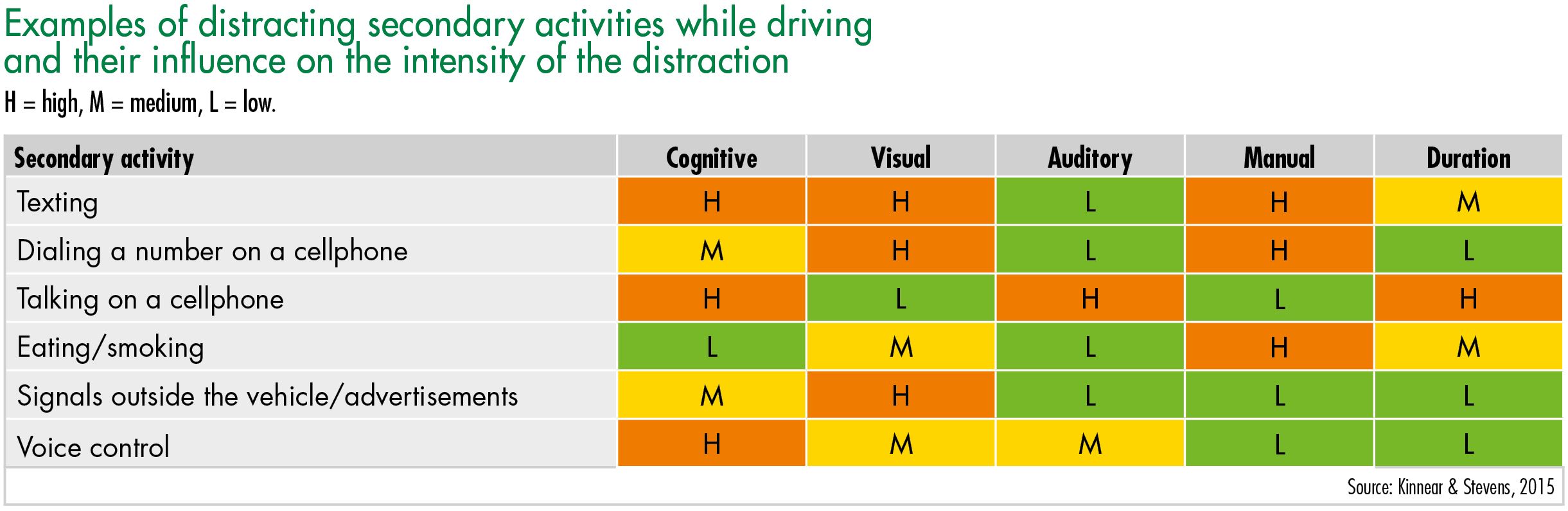

A survey conducted back in 1995 involving truck drivers who had been involved in a traffic accident gave an indication of the extent to which distraction, stress and fatigue play a role. Of the 55 drivers who had suffered an accident, 15 indicated “fatigue” as the reason for the accident, followed by ten drivers who specified being in a rush or under time pressure as the reason for the accident. Eight drivers also stated that they had become distracted by external stimuli. With regard to their own psycho- physical state immediately prior to the accident, 21 respondents stated that they felt “angry,” 17 said they felt “anxious,” 12 said they felt “tired” and ten said they felt “aggressive.” This clearly indicates that the behavior of drivers at fault in an accident and their frame of mind definitely play a role in the occurrence of accidents, even if these factors are not reflected in accident statistics. In 2013, the British Department for Transport reported that driver distraction had played a role in 2,995 accidents (three percent of all accidents). In 84 cases, these accidents were fatal (six percent of all accidents resulting in fatalities). Figures relating to accidents caused by driver distraction vary considerably across Europe. This can be attributed to a number of factors, including the fact that no single definition exists for the concept of “distraction” or “inattention.” According to Kinnear and Stevens, four types of distraction can be observed:

1. Cognitive or mental distraction occurs when a driver is mentally occupied with other activities that are not conducive to safe driving. This utilizes mental resources that are actually required for safe driving.

2. Visual distraction occurs when the driver is not looking at the road because they have shifted their attention to the radio, cellphone, advertisements outside, etc.

3. Auditory distraction refers to when a driver turns their attention to a noise. This type of distraction is often associated with another: When a driver tries to follow a conversation, which ties up their cognitive resources. That said, audible warnings emitted by the vehicle can focus the driver’s attention on the vehicle status.

4. Manual distraction refers to removing one or both hands from the steering wheel in order to perform other activities such as eating, drinking or operating devices.

Of course, the different types of distractions are inextricably linked. The extent to which the distraction impacts safe or unsafe driving is also related to the intensity of the distraction, the driving situation (stopping at a red light vs. very dense traffic) and the time (such as a simultaneous unexpected event). The Table below presents some examples of common secondary activities in terms of the impact they have on the type of distraction and the duration for which the driver would likely be distracted.

Multi-tasking is a myth

The reason why distractions are particularly dangerous for vehicle drivers is that people cannot do different things at the same time. When people attempt to multi-task, the individual activities impede each other. This is because when we multi-task, the brain cannot focus on both tasks simultaneously and instead continuously switches back and forth between the requirements, thereby impairing the performance of both tasks as the mind tries to distribute its attention resources. Since driving is a complex task that in itself requires multiple cognitive processes, performing an additional task while driving means that drivers no longer have the required attention resources to devote to the task of driving. This leads to processing errors and, in turn, loss of control over the actual task of driving, which puts the driver and all other road users at high risk.

Professional drivers in particular often have to deal with integrated vehicle technology. They spend a lot of time in their vehicles and are often under time pressure. A study conducted in 2009 (Olson et al.) reported that in 56.5 percent of safety-related incidents, drivers were engaging in a secondary activity while driving. Furthermore, the likelihood of a critical event occurring while the driver is texting increased 23-fold.

Opportunities to promote good health among professional drivers

The changes to the job description of professional drivers described above are resulting in a number of specific psychological and physical work pressures and, in turn, an increased risk of health complaints and illnesses. The job profile and associated workplace conditions vary greatly and depend to a great extent on the goods being transported, the transportation route and the organization of work tasks. The fundamental stress factors that affect a large number of workplaces for professional drivers are worth repeating: inconvenient working hours/shift work; long driving times; time pressures; physical environmental stresses such as noise, exhaust gases and lighting conditions; monotony and social isolation in the workplace; long periods away from home; demanding IT-supported assistance systems; long periods of sitting and inactivity; vibrations; load handling; working with dangerous substances. These work stresses can result in sleep disorders, acute and chronic fatigue and, in turn, an increased risk of being involved in an accident.

Professional drivers often have a risky lifestyle in terms of their eating habits and tobacco consumption. A consequence of maintaining a static working posture at the steering wheel and the high physical strain are feelings of discomfort throughout the entire musculoskeletal system, particularly the back. Professional drivers have a significantly higher risk of degenerative disc disease in the lumbar column, cardiovascular disease, being overweight, stomach ulcers and bronchial carcinoma.

It is clear from this that the introduction of an occupational health management system for professional drivers would be very important in terms of maintaining performance and a sense of wellbeing, ultimately preventing an increased risk of accidents. However, the fact that professional drivers are inherently on the move and spend most of their working time away from their business premises makes it extremely difficult to implement conventional methods of promoting occupational health.

What is more, the shipping and transport industry in particular has a high number of small and micro-enterprises, which have so far been generally unwilling to introduce occupational health promotion systems. Occupational health promotion often plays just a minor role compared with occupational health and safety. Intensive education programs and networking with institutions involved in preventive work can help and motivate employers to become active in the field of health promotion. Another option is to initiate company-wide, sector- specific quality and health networks.

Existing concepts for mobile employees can also be applied to professional drivers. Examples of these include an occupational health guide who can be contacted by drivers on tour, targeted use of mobile health apps, contracts with fitness studios along the route, an “in-truck gym,” or support with healthy eating on the road (“packed lunch”).

In principle, health-promoting measures should always be based on the sources of stress identified. In a survey conducted by Michaelis, for example, general strategies for preventing tiredness at the wheel and information on healthy eating and reducing tobacco consumption were requested.

Given the special physical and psychological stresses faced by professional drivers, there is a clear need for action in terms of occupational health promotion for this occupational group.

Compared with an office- or factory-bound workforce, more creative ways of communicating with professional drivers need to be found. As a general rule, the amount of time required for measures should be proportionately deducted from the respective working hours. The measure most likely to achieve an improvement might be the introduction of easily accessible services involving few formalities, requirements and little prior knowledge at, for example, rest areas and truck stops.